Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

It’s said that some of Hollywood’s most famous monsters were inspired by pictures of creatures that live in the darkest reaches of the ocean. Indeed, the “alien” appearance of the denizens of the deep hasn’t inspired a conservation mindset like baby seals or breaching whales. Yet it’s their otherworldly appearances that inspire Stacy Alaimo, a leader of the blue humanities field and professor of English at the University of Oregon, to share images of these animals far and wide, inspiring new appreciation for the part of our planet we have explored less of than outer space.

Alaimo, who also serves as director of English graduate studies and is a core faculty member of the Environmental Studies program, is currently working on a new book titled “Deep Blue Ecologies: Science, Aesthetics, and the Creatures of the Abyss.” It explores the effects of beauty and aesthetics on deep-sea science and conservation efforts for the creatures that live there.

“What I’m trying to look at is the way in which the aesthetic can function to widen our terrain of concern so that as environmentalists we’re concerned about every creature to the very bottom of the ocean,” Alaimo said.

Alaimo has become one of the most prominent figures in the field of blue humanities, which combines the field of humanities — the critical study of the human world and society — with marine science and ocean ecologies. The field is gaining popularity as more people become concerned with the warming and acidifying oceans, as well as the absence of marine science in traditional environmental humanities. Alaimo advocates for combining the humanities with the sciences, specifically when discussing the deep sea because of its inaccessibility and lack of exploration.

A Beauty of Their Own

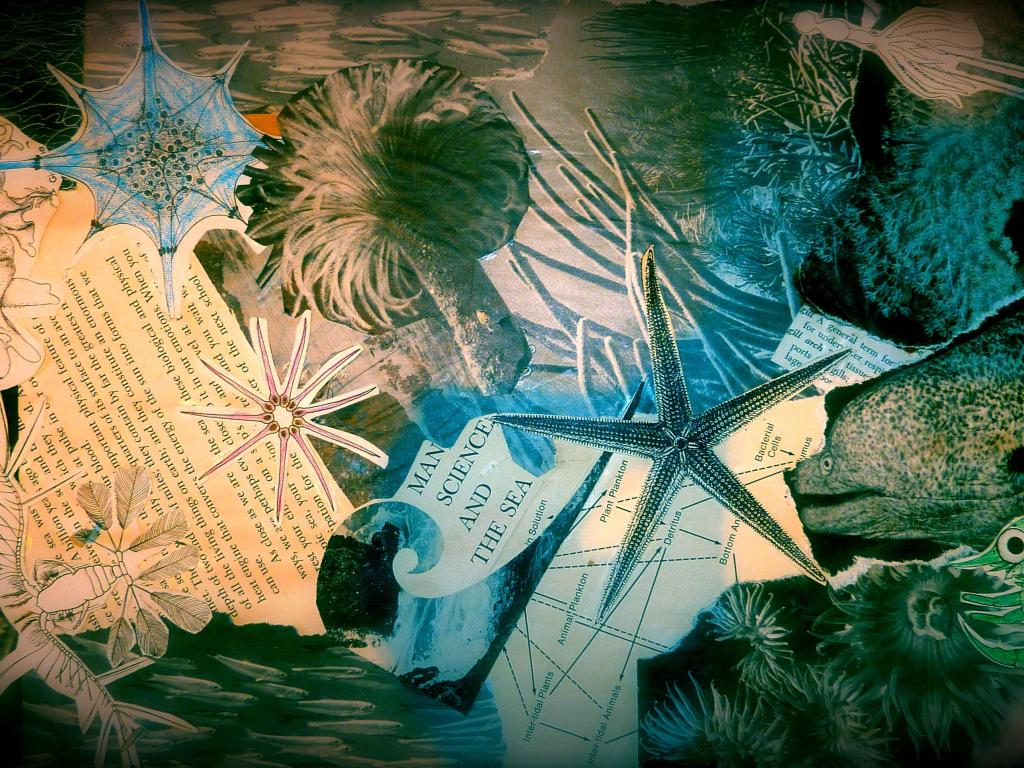

Alaimo’s research centers around one of the largest issues with establishing a connection between humans and deep-sea creatures: their “alien” characteristics and how they have been portrayed historically. She looks at images of deep-sea creatures from the Census of Marine Life and Claire Nouvian’s book, “The Deep,” to examine the creation of aesthetics through the use of light and positioning. Alaimo’s work outlines the danger of anthropomorphizing these distant creatures or applying human characteristics to non-human beings. In this case, however, anthropomorphizing these creatures actually results in some beneficial effects.

“Deep-sea creatures are often pictured as aliens from another planet, and I think that gets people interested in them because we’re all interested in novelty and weirdness and the surreal,” Alaimo said. “I think that can be positive, but the idea of the alien can also cut us off from any responsibility.”

If we consider these creatures merely ugly aliens from another realm, it discourages conservation and stewardship of the waters where they make their homes.

Adding another layer of complexity, Alaimo is exploring the social justice impact created by these artistic photographs. “One of the things I am interested in, in terms of thinking about this topic from a social justice perspective, is the idea of who the spectator is, who is the ‘we’,” Alaimo said. “So, when these images of deep-sea creatures are circulated, it is another kind of colonialist vision. How can I be concerned about these fish across the world in the deep seas that aren’t part of my life?”

Viewing images of deep-sea creatures in this way — a picture book of unrelatable animals on your coffee table — promotes a detached world, one which is absent of our inflictions on the planet and therefore does not require conservation. As her book comes together, Alaimo is examining the dichotomy of showing images of these creatures to promote conservation efforts while simultaneously avoiding the reduction of these animals to pretty pictures devoid of context.

These incredibly complex issues of artistic and aesthetic rendering and colonialist perspectives are concepts Alaimo enjoys working with because of their intricacy. It’s Alaimo’s specialty to turn preconceived notions on their heads. “I always try to work from a place where I can’t figure it out conceptually, ethically, politically. I always try to go to the spots that are really difficult and that’s where I think the work happens.

“The fact that most of the ocean is inaccessible to humans and that the inhabitants of these far reaches are often described as “alien” would seem to place them beyond the reach of human comprehension, ethics, and politics,” she said. “But rather than alienating people from the depths, the aestheticized captures of abyssal creatures can inspire the desire to imagine multi-species perspectives.”

"Envisioning the global oceans as populated by myriad unfathomable species, oscillating between a sense of aesthetic intimacy with these life forms and the impossibility of knowing their perspectives and their vast habits, makes the practice of imaginative mapping, speculating, and even design, a mode of environmental care and concern." — Stacy Alaimo